Wednesday, 2 March 2022

PLEASE BABY PLEASE - IFFR 2022 review

Friday, 16 July 2021

WITCHES OF THE ORIENT review

It's certainly jarring by modern standards to see such an un-PC approach to coaching, and alongside the footage of Daimatsu relentlessly hurling balls at his team, it stands as both a relic of a different time and a (not excused) display of how he pushed them to greatness, training them 6 days a week, 51 weeks a year. Maybe it's Stockholm syndrome or just the ability to look back on their youth with fondness, but the team all remember the barbs and nicknames in good humour, and have a lot of praise to offer for Daimatsu.

The film follows the team's humble beginnings from the Nichibo Kaizuka factory - with players graduating from the factory floor to becoming part of the sports team - all the way through their success at the World Volleyball Championships and towards the prospects of bringing home Olympic gold. As fate would have it, Tokyo was chosen as the host city for the 1964 Olympics, marking the first time television would be broadcast from Asia to the United States as well as the introduction of two new Olympic sports, judo and volleyball. With huge political and cultural ramifications as well as national pride at stake - particularly when the volleyball team were to face their biggest rivals, the USSR, in the final - the importance of winning wasn't lost on these women.

Paralleling their success with that of Japanese industry, Faraut employs a number of energetic montages to show how the team was trained to win. Cut together to create a collage of animation, old footage and a propulsive new synth soundtrack courtesy of Grandaddy's Jason Lytle, Witches of the Orient resembles something akin to a music video Spike Jonze would have made at the turn of the millennium. The volleyball anime that shows them leaping like superheroes is incredibly fun to watch and gives the film a truly unique way of telling the story of these women. Likewise the footage of them training, showing the relentless regimen they were under, has a rhythmic quality that pulls you into their world.

Where the film does hit a wall, somewhat, is in the modern day interviews with the players. We see their family lives as doting grandmothers (and in one case a still active love for volleyball), but these sequences do go on longer than necessary and stop the momentum the film builds with its archive material. Faraut's approach is about offering these clashes in speed and sources, switching gears from a Portishead scored montage to a more sedate, formal documentary 'slice-of-life' style, but an argument could be made that had he presented a documentary that was solely comprised of just the archive, all the high points would remain intact.

In the same way his 2018 tennis doc In the Realm of Perfection was less an expose of John McEnroe as a public figure of some repute, and more a dissection of the mechanics of how McEnroe was such a skilled athlete, where this film succeeds is in selling the Nichibo Kaizuka team as a force to be reckoned with. As the film sets into the final showdown against the team from the Soviet Union, the reveal of the restoration work on the original film is incredible, looking and sounding as good as new. I'm sure the original footage was passable, but the attention it's been afforded gives this film the sporting climax it deserves. Director Julian Faraut has crafted a truly fascinating documentary on the young lives of these women and the pressure they were under to succeed from the powers that be. Inventively presented and compelling, Witches of the Orient is a gripping, joyous experience.

Verdict

4/5

Witches of the Orient is in cinemas now, and available to stream at home via ModernFilms.com.

Thursday, 10 June 2021

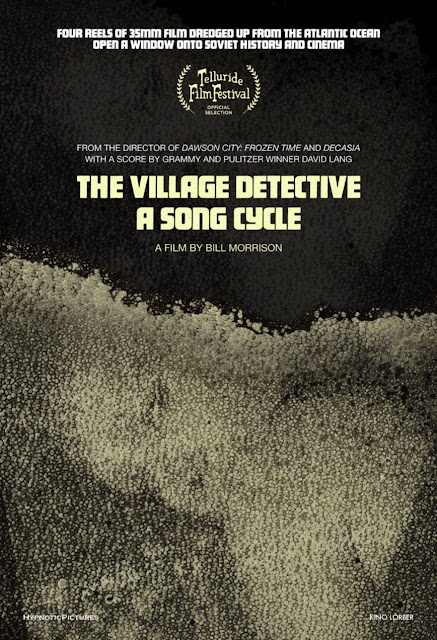

THE VILLAGE DETECTIVE: A SONG CYCLE - ROTTERDAM INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2021 review

Part of the Cinema Regained strand from this year's IFFR was Bill Morrison's The Village Detective - A Song Cycle. Picking up where he left off with Dawson City: Frozen Time, the story of Morrison's latest film begins with an email he received from the great, sadly departed composer Johan Johansson, who heard about a canister containing four reels of film that had been dredged up from the sea bed by a lobster trawler off the coast of his native Iceland. With hopes from Morrison and the National Film Archive of Iceland that it would be a lost silent classic, it turned out to be Derevenskij Detectiv (The Village Detective), a 1969 Soviet film that was considered neither lost or rare. Diving headfirst into the history of the film and its star Mikhail Zharov, Morrison uses clips from "lost" films like 1917's The Fall of the Romanoffs and from Zharov's many big screen credits to chart his career and the history of Soviet cinema.

Considered at the time to be a star on the same level as Humphrey Bogart or Clark Gable, here Zharov stands in for all the forgotten actors from cinema's first 50 years, whose credits are reduced to a potted history in film history textbooks. Donning wigs and beards to play everything from prisoners of a regime to noted dignitaries, it's fascinating to watch his career across the decades, from young supporting actor in 1915's Tsar Ivan the Terrible to his role as Aniskin in The Village Detective, that became a regular role towards the end of his life.

As the film plays out for us - including the sprockets that fill the frame - and the image distorts, it's almost impossible to decipher, but it's that unique power of cinema language that means we want to. Piecing the fragments together in our brain in order to understand the narrative (helped by David Lang's accordion score), what we're watching in its purest form is a collection of still images that lay underwater for decades, but that with the help of a bright bulb and some forward motion are able in all its damaged, corrupted glory to still tell us a story. It's a brilliant, breathtaking experience that will fill you with immense nostalgia for the format and a renewed hope that these films aren't lost to time. No-one's going to find a DCP drive at the bottom of the ocean in 50 years, and if they do it's not going to be of much use to anyone, but here, as we reach the end and watch the image deteriorate before our eyes, it's a beautiful thing to watch.

Verdict

5/5

Tuesday, 8 June 2021

IFFR - ROTTERDAM INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2021 (JUNE EDITION)

With real world commitments taking hold of my life a bit more than the February edition, I didn't get to see as many of the June edition's films as I would have liked, but still managed to delve into what these new strands had to offer. Separated into Harbour, Bright Future, Short & Mid-length and Cinema Regained, it was in the last, most experimental, film history led strand where I found the most to enjoy.

Beginning with Nicolas Zuckerfeld's There Are Not 36 Ways of Showing a Man Getting on a Horse, which is pretty much what you'd expect it to be and then some, the film starts with an extended montage of men getting on horses, all clipped from classic Westerns of Hollywood's golden age and complete with cowboys, the cavalry, "Indians" and assorted lawlessness. For any fan of cinema, it's quite thrilling to see this selection of old Hollywood horse operas, and as the doc's scope expands out to a wider view of Hollywood storytelling, pairing up moments from years apart (covering the Raoul Walsh films 1915's Regeneration, 1964's A Distant Trumpet and many in-between) to show how much reliance there is on a set formula. The film takes a turn half way in, as Zuckerfeld's narration moves the film into a more academic realm as he discusses Edgardo Cozarinsky's book, Cinematografos, and delves into the Raoul Walsh quote that serves as the film's title. There Are Not 36 Ways of Showing a Man Getting on a Horse works best as an art film, the very wordy canter of the second chapter a dramatic shift from the visual gallop of the first, and is probably for film history buffs only.

My second film of this extended festival came from the Harbour segment, the big draw being a debut acting role for Zack Mulligan, AKA one of the subject of Bing Liu's excellent Oscar-nominated skateboarding documentary, Minding the Gap. With opening shots of American cornfields setting the scene, Death on the Streets introduces us to Mulligan as Kurt, a down on his luck almost 30-something with a wife, two kids and a lot of money problems. Doing his best to keep his head above water with day work in the local farming industry, he's a quiet man with enough dignity or foolhardiness to turn down the help offered by local well-wishers, including his father in law who creates fake odd jobs around his house in order to give Kurt a hand-out.

In no small part due to the heavy emotional baggage that comes with Mulligan after Minding the Gap, he acquits himself well in a role that has no flashy moments, only one man's quiet desperation as he looks upon the rock face of the gig economy. The film is awkwardly weighted, spending two thirds of its runtime setting up its last act that, although it limits the appearance of the impressive Katie Folger as Kurt's wife, actually gets close to delivering the message it's aiming for, with despair mixed with hope coming in the form of homelessness. Emotionally pitched somewhere close to Kogonada's Columbus and touching on some similar themes to Chloe Zhao's Nomadland, it's let down by a lack of narrative drive and some truly amateurish acting from the supporting players. A sharper script and a more ruthless editor might have given Mulligan a better film for his debut, but he's a likeable screen presence you want to root for.

With the promise that you'll never watch Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street in the same way again, The Philosophy of Horror: A Symphony of Film Theory uses old reels of the first two films to create something new, different and strangely compelling to watch. Manipulated, dyed, blacked out with pen and looking generally like it's been stored in a high school boiler room, this isn't a print that's in pristine condition, and is merely used as a vehicle for a deeper dive into film theory, featuring clipped excerpts from Noel Carroll's Philosophy of Horror book. Although a similar effect could have been achieved by using another classic horror film, like, Sam Raimi's The Evil Dead, for example, the whole reason why Freddy Krueger's first outing works in this context is the dreamlike trance it draws you into. Featuring no music or dialogue from the actual film and soundtracked by Ádám Márton Horváth's grungey, guitar feedback led soundscape, it's quite easy to be drawn into this weird world of freeze frames, repeated images and distorted, strobing faces.

With mouths agape like they're silently screaming out for help, the film occasionally moves on for a few frames, allowing Heather Langenkamp's fear to project towards us as the boogeyman looms into view. With its rhythmic, pulsating score and vivid colours, whatever has been done to this strip of celluloid has turned it into something almost Lovecraftian in the process, whilst also mimicking and replicating the mania of a dream state, albeit an occasionally nightmarish one. It's self-indulgent, using up portions of its runtime for an opening overture and an intermission, and although it might not deliver any coherent analysis on Wes Craven's horror masterpiece (and with a surprising lack of Krueger on screen), it's a bold, impressively realised visual experiment.

Last up from the Cinema Regained strand was Bill Morrison's The Village Detective - A Song Cycle. Given the treatment of the source material in the last film I'd seen, I went into Bill Morrison's film to find startling similarities, although in this case the distorted film was truly breathtaking to see come to life. Picking up where he left off with Dawson City: Frozen Time, the story of Morrison's latest film begins with an email he received from the great, sadly departed composer Johan Johansson, who heard about a canister containing four reels of film that had been dredged up from the sea bed by a lobster trawler off the coast of his native Iceland. With hopes from Morrison and the National Film Archive of Iceland that it would be a lost silent classic, it turned out to be Derevenskij Detectiv (The Village Detective), a 1969 Soviet film that was considered neither lost or rare. Diving headfirst into the history of the film and its star Mikhail Zharov, Morrison uses clips from "lost" films like 1917's The Fall of the Romanoffs and from Zharov's many big screen credits to chart his career and the history of Soviet cinema.Considered at the time to be a star on the same level as Humphrey Bogart or Clark Gable, here Zharov stands in for all the forgotten actors from cinema's first 50 years, whose credits are reduced to a potted history in film history textbooks. Donning wigs and beards to play everything from prisoners of a regime to noted dignitaries, it's fascinating to watch his career across the decades, from young supporting actor in 1915's Tsar Ivan the Terrible to his role as Aniskin in The Village Detective, that became a regular role towards the end of his life.

As the film plays out for us - including the sprockets that fill the frame - it's almost impossible to decipher, but it's that unique power of cinema language that means we want to. Piecing the fragments together in our brain in order to understand the narrative (helped by David Lang's accordion score), what we're watching in its purest form is a collection of still images that lay underwater for decades, but that with the help of a bright bulb and some forward motion are able in all its damaged, corrupted glory to still tell us a story. It's a brilliant, breathtaking experience that will fill you with immense nostalgia for the format and a renewed hope that these films aren't lost to time. No-one's going to find a DCP drive at the bottom of the ocean in 50 years, and if they do it's not going to be of much use to anyone, but here, as we watch reach the end and watch the image deteriorate before our eyes, it's a beautiful thing to watch.

____________________________________________________________________

And with that, sadly, my time at IFFR draws to a close. This was my first year taking part in the festival, and although I was only able to visit it in a virtual space, I look forward to hopefully joining them in person at some point in the near future. Overall, both outings had a great selection of new, exciting pieces of cinema, including many that I look forward to seeing find an appreciative audience that, with any luck, I'll be a part of.

Sunday, 21 February 2021

THE DOG WHO WOULDN'T BE QUIET/EL PERRO QUE NO CALLA - Rotterdam International Film Festival review

Making its debut at this month's IFFR, the award winning The Dog Who Wouldn't Be Quiet (El Perro Que No Calla) follows Sebastian (Daniel Katz) as he tries to placate his neighbours and workplace when his dog, suffering from immense loneliness, creates a noise issue by crying out in his absence. Choosing to completely change his way of life, we follow Sebastian as he navigates his way through and acclimatises to a number of unexpected personal and societal twists and turns.

Directed and co-written by Argentinian director Ana Katz, this monochrome social-realist fantasy depicts key moments in the life of Sebastian (Daniel Katz), a graphic designer and owner of an 8 year old dog who can't bear to be without him, to the point where he sobs until he returns. Sebastian is a shy, caring man who only wants the best for his pet and everyone around him, and is so unshackled to his own sense of emotional wellbeing that he's willing to change his life to keep others happy, including moving to a remote farm where he can live with his dog in peace. But when tragedy strikes and his life is up-ended once more, he finds himself at a loss, unsure of what direction his life will take and how much control he has in it.A film about facing life's many unexpected, often suffocating moments of rigour head on, The Dog Who Wouldn't be Quiet continually shifts from the path you think it's on, giving lovely, sweet scenes of this average man's life that feel all too relatable, even when pushed into the realm of satirical sci-fi. A quiet, emotional, meditative experience. Enjoy.

Verdict

5/5

Saturday, 20 February 2021

WITCHES OF THE ORIENT/LES SORCIERES DE L'ORIENT - Rotterdam International Film Festival review

One of the highlights of the recently wrapped IFFR Rotterdam International Film Festival (that is, until the second leg begins in June), French director Julian Faraut's Witches of the Orient (Les Sorcieres de L'Orient in its original French) is a fascinating blend of archive materials and volleyball anime - a subgenre that sprang up at the height of the team's success and that is still being made today - along with new interviews with the team, now all in their seventies. Gathered around a grand roundtable - the setting for a catch up meal rather than an in depth interview - Faraut nods to the level of fame and hero-worship they once received by introducing each player with stylised on-screen graphics. More appropriate for characters from a Saturday morning cartoon that a group of septuagenarians, these intro's reveal the taunting, often cruel nicknames they played under (Blowfish, Horse, Kettle, and so on), bestowed upon them by their coach, Hirofumi 'The Demon' Daimatsu, based on how he judged their physical appearances.

It's certainly jarring by modern standards to see such an un-PC approach to coaching, and alongside the footage of Daimatsu relentlessly hurling balls at his team, it stands as both a relic of a different time and a (not excused) display of how he pushed them to greatness, training them 6 days a week, 51 weeks a year. Maybe it's Stockholm syndrome or just the ability to look back on their youth with fondness, but the team all remember the barbs and nicknames in good humour, and have a lot of praise to offer for Daimatsu.

The film follows the team's humble beginnings from the Nichibo Kaizuka factory - with players graduating from the factory floor to becoming part of the sports team - all the way through their success at the World Volleyball Championships and towards the prospects of bringing home Olympic gold. As fate would have it, Tokyo was chosen as the host city for the 1964 Olympics, marking the first time television would be broadcast from Asia to the United States as well as the introduction of two new Olympic sports, judo and volleyball. With huge political and cultural ramifications, as well as national pride at stake - particularly when the volleyball team were to face their biggest rivals, the USSR, in the final - the importance of winning wasn't lost on these women.

Paralleling their success with that of Japanese industry, Faraut employs a number of energetic montages to show how the team was trained to win. Cut together to create a collage of animation, old footage and a propulsive new synth soundtrack courtesy of Grandaddy's Jason Lytle, Witches of the Orient resembles something akin to a music video Spike Jonze would have made at the turn of the millennium. The volleyball anime that shows them jumping like superheroes is incredibly fun to watch and gives the film a truly unique way of telling the story of these women. Likewise the footage of them training, showing the relentless regimen they were under, has a rhythmic quality that pulls you into their world.

Where the film does hit a wall somewhat, is in the modern day interviews with the players. We see their family lives as doting grandmothers (and in one case a still active love for volleyball), but these sequences do go on longer than necessary and stop the momentum the film builds with its archive material. Faraut's approach is about offering these clashes in speed and sources, switching gears from a Portishead scored montage to a more sedate, formal documentary 'slice-of-life' style, but an argument could be made that had he presented a documentary that was solely comprised of just the archive, all the high points would remain intact.

In the same way his 2018 tennis doc In the Realm of Perfection was less an expose of John McEnroe as a public figure of some repute and more a dissection of the mechanics of how McEnroe was such a skilled athlete, where this film succeeds is in selling the Nichibo Kaizuka team as a force to be reckoned with. As the film sets into the final showdown against the team from the Soviet Union, the reveal of the restoration work on the original film is incredible, looking and sounding as good as new. I'm sure the original footage was passable, but the attention it's been afforded gives this film the sporting climax it deserves. Director Julian Faraut has crafted a truly fascinating documentary on the young lives of these women and the pressure they were under to succeed from the powers that be. Inventively presented and compelling, Witches of the Orient is a gripping, joyous experience.

Verdict

4/5

Saturday, 13 February 2021

ROTTERDAM INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2021

Drawing to a temporary close last weekend, the 50th edition of the Rotterdam International Film Festival (better known as IFFR) switched up its format for these pandemic stricken times, mirroring most of the other big-hitter festivals by shifting online, but rather than offering a reduced festival Rotterdam is setting itself apart by expanding and splitting in two - a February programme and another, more optimistic instalment scheduled for June that aims to incorporate outdoor screenings an in-cinema events across The Netherlands that will highlight the festival's rich history and reputation of championing emerging filmmakers from around the globe.

Incorporating different areas of competition - the Tiger Competition, the Big Screen Competition and the Tiger Shorts Competition - that comprised 30 features and nearly the same amount of shorts, the winners were announced as part of the closing night celebrations, that also honoured director Kelly Reichardt with the second annual Robby Müller Award for her work in film. With so many films on offer it's simply impossible to take them all in - I missed out on the new Mads Mikkelsen film Riders of Justice that I was hoping to see - but along with the switch to a virtual format there's a newfound joy in going into screenings (at home) blind with no pre-conceived ideas or word of mouth buzz that you'd expect at old-fashioned "physical" festivals, apart from the occasional mention on Twitter that's not always a sure-fire benchmark of quality.

Directed by Félix Dufour-Laperrière, French animation Archipelago/Archipel creates an almost trance-like world of imagery and poetry, using natural landscapes and archive film as part of their palette to aide the animation of the imagined islands of the title. Using a variety of techniques from simple line drawings to rotoscoping, my personal favourite element was the inverse silhouettes it employed that draw the eye like the keyhole of a door to another world. It's a technique used before, perhaps most notably in the Pixar short Night and Day, but accompanying the dialogue that's delivered as if it's a confessional diary entry written by a warring couple ("You don't exist", "You're wrong"), there's a deeper emotional weight to it. I'll be honest that it's the visuals that make Archipelago a compelling experience, and even if you do check out from the continuing narrative as you're entranced by a rotoscoped swimmer or old film brought to new life with some animated enhancements, the cyclical nature of the film is forgiving.

Drawing way too much inspiration from Todd Phillips' Joker, The Cemil Show follows a shopping mall security guard (Ozan Çelik) as he lives out his fantasy of being a movie star by studying and copying the performance of his idol, Turgay Goral, the villain in a series of films in the 1960s. By chance, Cemil's co-worker Burcu (Nesrin Cavadzade) happens to be Goral's daughter, giving Cemil access to a VHS archive of his past performances that will push the already unhinged wannabe actor over the edge of insanity. As his delusion becomes a psychotic desire to become Goral's villain for real, Cemil puts the lives of Burcu and the original film's director in serious danger.

It's a sad, joyless film with a thoroughly unclear message that's drastically and un-ironically hampered by its own desire to ape Joaquin Phoenix's Oscar winning turn as Arthur Fleck in Joker, not helped at all by budgetary limitations that mean a large proportion of scenes are shot on the empty level of a multi-storey car park. There's some surprisingly effective character work by Cavadzade, as Burcu becomes increasingly fed up with her lot in life, but the performance of Çelik as an average Joe turned homicidal madman just isn't convincing.

Dutch director David Verbeek's Dead and Beautiful follows the nocturnal activities of a group of young, wealthy urbanites as they explore the benefits of their newfound blood lust on the streets of Taiwan. Waking up after a spiritual cleansing with fangs, they retreat to the empty luxury penthouse owned by one of their billionaire fathers and plot how best to make the most of life as a vampire. Equal parts socio-political and sociopathic, Dead and Beautiful taps into the 80's yuppie excess of Joel Schumacher's The Lost Boys and Flatliners. It's a pleasingly inventive update on the genre that treats vampirism like a designer drug, starring a group of characters that are blinded by their immense privilege and contempt for everyone else.

Nodding heavily towards Ana Lily Amirpour's A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, Alice Lowe's Prevenge and Abel Ferrara's The Addiction, Black Medusa stars Nour Hajri as Nada, a near mute young woman who picks up random men in the nightclubs of Tunis in order to violently and sadistically murder them. When her workmate Noura extends an offer of friendship, Nada rejects her, until a dangerous turn of events sees her calling on her in her time of need.

Presented as a 'Tale in Nine Nights', it's a mystery as to why Nada is doing this, although the sexual humiliation she inflicts on these men (such as penetrating them with a broom handle) hints towards her motivation. Shot over 12 days with a small crew, it's a gorgeous black and white that features a number of outdoor day-lit scenes that show off the vibrancy and beauty of Tunis. Despite being almost entirely mute and carrying a blank, numb expression, Hajri's a compelling presence on screen and manages to convey a lot with a simple stare. A troubling look at a woman taking action against the repulsive side of life in her city, Black Medusa is a dark, catharsis-free revenge fantasy.

More than 50 years after competing at the Tokyo Olympics, the surviving members of the Nichibo Kaizuka volleyball team are brought back together to reminisce about their worldwide success that lead to them being dubbed the Witches of the Orient, and the rigorous training they were put through by their head coach, Hirofumi 'The Demon' Daimatsu. Using some of the vintage volleyball anime that became prevalent after their success on the world stage and footage from their training sessions, director Julian Faraut has crafted a truly fascinating documentary on the young lives of these women, and the pressure they were under to succeed.

Cut together to create a collage of animation, old footage and a new propulsive soundtrack, Witches of the Orient (or to give it its original French title, Les Sorcières de l'Orient) resembles something akin to a Spike Jonze music video montage, but with a deeper emotional journey served with its use of the present day interviews with the women, now in their seventies. As the film sets into the final showdown against the team from The Soviet Union, the reveal of the restoration work is incredible, making it a gripping, joyous experience to watch. Inventively presented and compelling, Witches of the Orient is a fantastic achievement in documentary filmmaking.

In Karen Cinorre's dreamlike Mayday, Grace Van Patten stars as Ana, a waitress at a wedding who in the middle of a storm warning is transported into a new world where soldiers are falling from the sky and the world she knew is out of order. Teaming up with a troop of young women lead by Mia Goth's Marsha, they listed to radio signals from their beached submarine and fend off the danger posed by the continuing appearance of new soldiers around them.

A 'girl's own adventure' with a World War II meets Wizard of Oz slant to it, Mayday throws a lot of creativity at the screen and not all of it sticks. The world they're in is a befuddling one, and although unexpected dance routines and synchronised swimming might make for charming interludes, it's hard to see what relevance they have to the story. Van Patten, an absolute star on the rise after solid performances in Noah Baumbach's The Meyerowitz Stories and Dolly Wells' Good Posture, serves the script well and has a great interplay with Mia Goth, but there's not enough substance to make this feel more than just a flight of fancy.

The final feature I was able to see and one of the absolute delights of the festival was Ana Katz's The Dog Who Wouldn't Be Quiet/El Perro Que No Calla, following a young man, Sebastian (Daniel Katz), as he tries to placate his neighbours and his workplace when his dog suffers immense loneliness when he's not there and cries out until he returns. The deserved winner of the Big Screen Competition prize, it's a fascinating and completely unpredictable story that jumps ahead to key moments in Sebastian's life as it takes a number of unforeseen turns, including a segment that sees characters forced to wear breathing helmets and obey a strict protocol to stay below 4ft. Science fiction that's utterly feasibly given the 2020 we just had, it's a film that continually shifts what you think it is, giving lovely, sweet moments of unexpected comedy to balance the rigours of Sebastian's life.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------